Resource Allocation

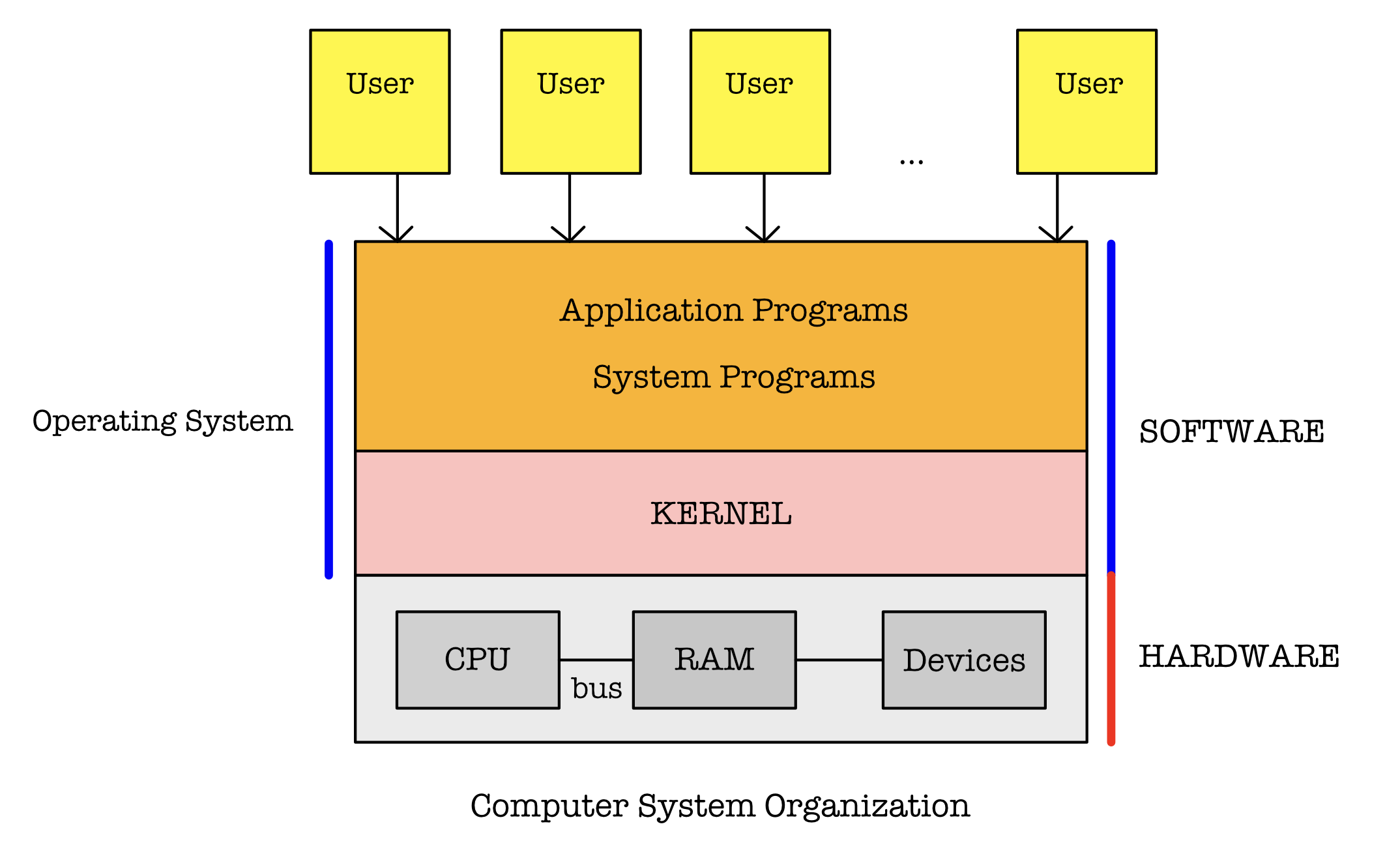

What is an OS?¶

An intermediate program between the users of a computer and its hardware. It does:

- Resource allocation and coordination: manages I/O requests, interrupts, hardware

- Controls program execution: storage hierarchy manager, process manager

- Limits program execution: prevents illegal access to hardware and improper hardware usage and ensures security

An OS can be broadly divided into three parts:

- Kernel

- System programs

- User programs

Booting (NT)¶

- Hardware initiated, user presses a physical button to load the BIOS (located in a dedicated ROM that comes built in to a computer)

- BIOS loads the Master Boot Record, which contains info about disk partitions and bootstrap code.

- Bootstrap code points to the bootloader, which is in the bootsector of the disk, which in turn points to the entry point of the OS code. If there are multiple OS, the bootloader asks the user to choose

- OS starts

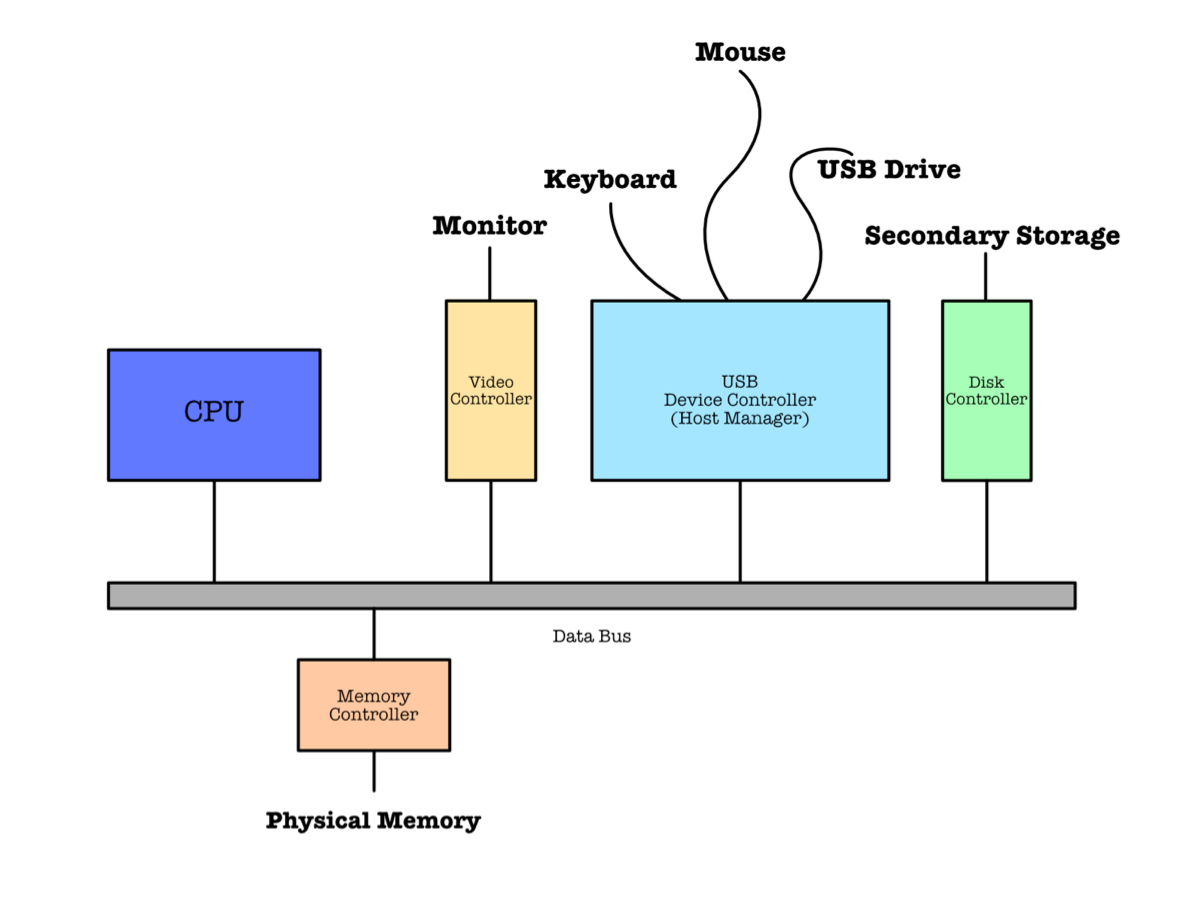

I/O Controllers¶

Each I/O device is managed by an autonomous hardware entity called the device controllers as shown in the figure below:

These controller devices are asynchronous and can execute instructions independently of the CPU

The following components make up a device controller:

- Registers — contains instructions that can be read by an appropriate device driver program at the CPU

- Local memory buffer — contains instructions and data that will be fetched by the CPU when executing the device driver program, and ultimately loaded into the RAM.

- A simple program to communicate with the device driver

An I/O operation happens data is transfered between the local memory buffer of the device controller and the device itself.

- Input: Device -> Buffer -> RAM

- Output: RAM -> Buffer -> Device

Drivers¶

A system must have device drivers installed for each type of device. This is a special program to interpret the behaviour of each type of device so that the OS can meaningfully communicate with it.

Device drivers can run in both kernel and user mode. Running in user mode is slower due to frequent sys calls, but safer if poorly written. Poorly written kernel mode drivers can wreak havoc on a computer.

The Kernel¶

The kernel is the heart of the OS. It operates on the physical space - it has full knowledge of all PA instead of VA and has complete priviledge over all hardware of the computer system

The only way to access the kernel code is when a process runs in kernel mode: controlled entry points. Hardware supported dual mode

The kernel can

- Interrupt other user programs

- Receive and manage I/O requests

- Manage other user program locations on the RAM, the MMU, and schedule user program executions

It consists of the following components:

- Vectored IRQ

- Prep Instructions

- Interrupt Handlers

- Scheduler (ProcTbl + Scheduler)

- Drivers

The kernel performs the following tasks:

Resource Allocation and Coordination¶

The kernel controls and coordinates the use of hardware and I/O devices.

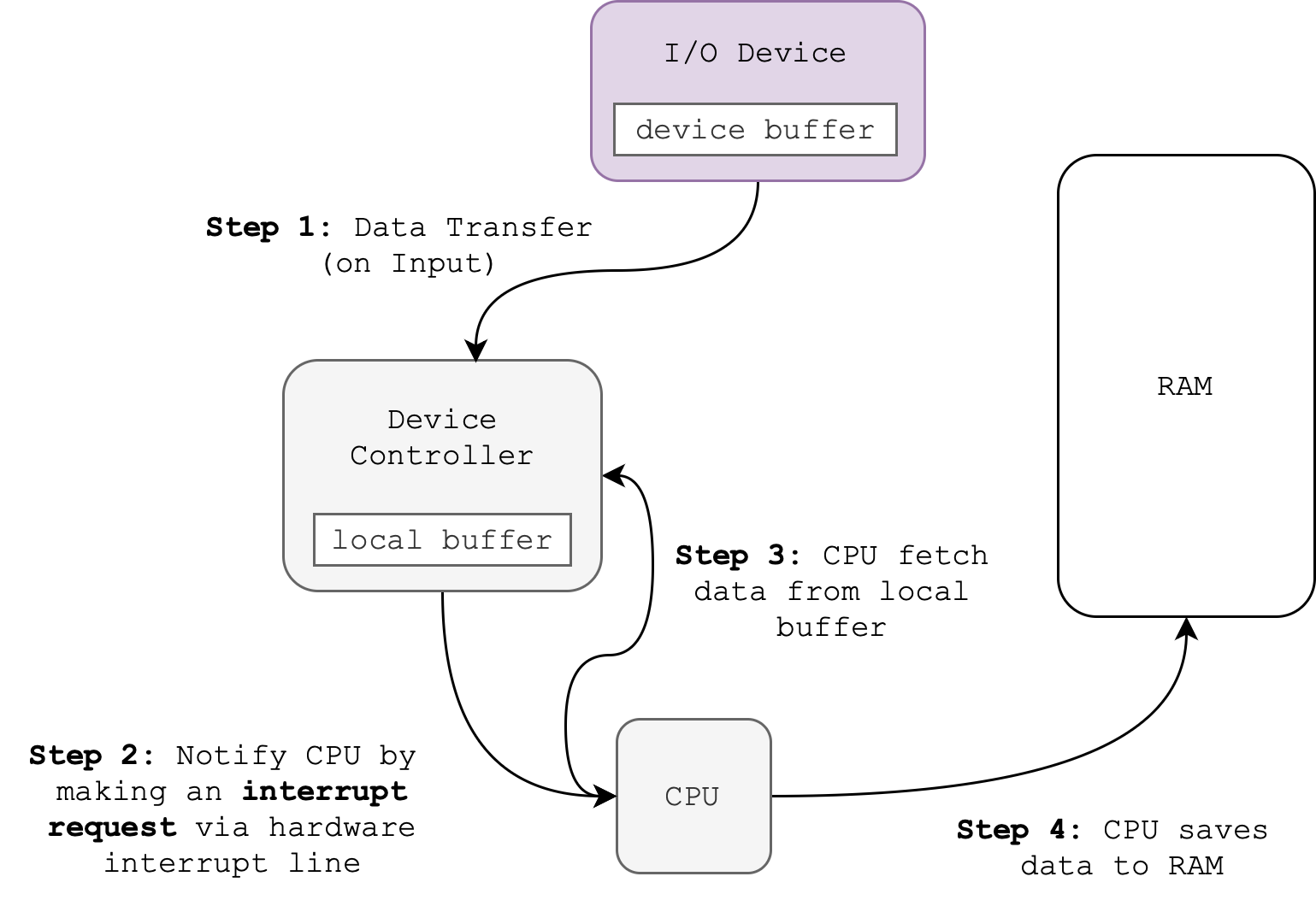

Interrupt-Driven I/O Operation¶

Hardware Interrupt¶

Triggered from I/O sources like mouse/keyboard

IRQ -> save registers to process table (for restoring) (the context) Transfer control to the appropriate interrupt service routine (JMP)

The Xaddr in the beta can be muxed to directly provide the correct address of the correct I/O handler. The X is a variable object!

Vectored Interrupt System¶

In a VIS, the interrupt signal includes an address, which serves as an offset to a table called the interrupt vector. This table holds the addresses of the routines needed to process specific interrutps.

This is useful when there are sparse I/O requests, but complex to implement

Polled Interrupt System¶

CPU scans devices to see if an interrupt request was made. Unlike vectored interrupt, there is no signal including the identity of the device sending the signal. This is done at periodically/at a fixed interval.

This is bad when there are sparse I/o requests, but simple to implement

In case of multiple interrupts, the kernel scheduler decides which requests to service first.

Overview of an I/O Interrupt¶

- I/O Device receives physical input

- Device controller triggers an IRQ

- CPU senses the IRQ and jumps to the interrupt handler

- Handler saves the current process' state and determines the source of the interrupt (vectored/polling) and performs the necessary handling

- This involves transferring the data from the device controller buffer to the RAM

- The handler clears the IRQ signal

- Restores the state of the process which it interrupted and performs a jump to the exception pointer

- They are async

Software Interrupts (Traps, Sync)¶

System calls and traps triggered by instructions themselves. Some software traps can be blocking. Lower prio than hardware interrupts

An SVC and an IRQ can be combined:

- SVC made to load data from disk

- After some delay, the SVC is served and the SVC handler asks disk controller to load data and returns to the user process

- After more delay and the disk controller has loaded the file, it triggers an IRQ

- After some more delay, this IRQ is handled, and the loaded file is transferred from the disk buffers to the RAM

Reentrancy¶

A re-entrant kernel allows multiple processes to make SVCs simultaneously without leadnig to consistency issues in the kernel data structures. A non re-entrant kernel only serves an interrupt if the current process is in user mode.

An SVC is a voluntary interrupt

Any processes making an SVC is therefore halted in a non-reentrant kernel if another process is already in kernel mode. Interrupts are disabled during the time a context switch or state saves or restores are being peformed

Preemption¶

A pre-emptive kernel allows the scheduler to interrupt processes in kernel mode to execute the highest priority task first (strong preemptive scheduling policy)

In a non preemtive kernel, a process cannot interrupt another process forcibly

A re-entrant non pre-emptive kernel will not allow a process in KM to be interrupted!

A non re-entrant pre-emptive kernel will allow a process in KM to be interrupted, but won't allow any other process to go into KM because the first process is blocking

Timed hardware interrupts¶

A user process cannot be allowed to take control of the CPU indefinitely, thus a hardware scheduler invokes IRQ at set periods so that the OS (kernel) can take the control of the CPU back.

There is a counter that is initially set by the kernel itself, and it is continuously decremented whenever the clock ticks, and when it reaches 0, an interrupt is triggered.

Exceptions¶

Exceptions are software interrupts. The CPU may use a pre built event vector table to handle exceptions (catch blocks?)

Each exception has an ID and a vector address associated with its handler's entry point. They also have a prioerity (lower priority number = more important)